In his 2011 Presidential Study Directive 10, Barack Obama declared, “Preventing mass atrocities and genocide is a core national security interest and a core moral responsibility of the United States.” He sought, in this area of humanitarian concern at least, the unity of moral responsibility and national security interest in a policy of prevention. He briefly elaborated his reasoning as follows: “Our security is affected when masses of civilians are slaughtered, refugees flow across borders, and murderers wreak havoc on regional stability and livelihoods. America’s reputation suffers, and our ability to bring about change is constrained, when we are perceived as idle in the face of mass atrocities and genocide.”

It seems unlikely that Obama’s rhetoric here did much to persuade anyone who was not already convinced about the importance of humanitarianism—that taking action to prevent mass atrocities is a sound priority for U.S. policy, indeed, a “core” priority. To say “our security is affected when masses of civilians are slaughtered” is merely to restate the proposition that prevention is a national security interest, which it may or may not be. That is the question. When “refugees flow across borders,” presumably fleeing violence, this could clearly affect U.S. national interests in some cases—but not necessarily in all cases. Atrocities certainly “wreak havoc” on local stability and livelihoods, but they may or may not have regional effects the United States is obliged as a matter of national interest to care about.

As for the reputational damage that idleness in the face of mass atrocities supposedly causes the United States, that would seem to hold mainly for those who already believe the United States should take action. The moral authority of the United States as an opponent of genocide and mass atrocities would indeed be compromised as a result of a failure to take preventive action when possible. But whether the United States has or should seek such moral authority is another question. If you have concluded that the United States has neither a moral responsibility to act to prevent atrocities nor a national interest in doing so—either in general or in a specific case—then you are likely to be willing to ignore claims about damage to your reputation coming from those who disagree with you. As for idleness constraining the ability of the United States “to bring about change,” how does it do so? One could argue—in fact, many do argue—that refraining from unnecessary humanitarian military intervention keeps America’s powder dry for those occasions when the use of force is necessary according to criteria of national interest.

President Obama, in short, was preaching to the choir—those who share his view about the “moral responsibility” of the United States to take action. That’s not necessarily a bad thing to do, but it offers little to those who would like to understand why the prevention of atrocities by and against others is something the United States must undertake as a matter of national interest. Obama offered no more than an assertion of national interest, leaving us with a humanitarian imperative one could accept for moral reasons or decline for practical ones—reasons of state, i.e., national interest.

Worse, Obama formulated his statement in such a way as to evade perhaps the hardest question arising out of this consideration of American moral responsibility and national interests: What happens when taking action to prevent atrocities actually conflicts with perceived U.S. national interests? This contradiction was nowhere more apparent than in Obama Administration policy toward Syria, where the prevention of atrocities came in second to the national interest Obama perceived in avoiding American involvement in another Mideast war.

Now, one could perform a rescue mission on Obama’s rhetoric by noting that he claimed preventing atrocities was “a” core national security interest and “a” core moral responsibility—not “the.” His statement thus implicitly acknowledges other such “core” interests—which, of course, he left unspecified. Presumably, these core interests and responsibilities may at times conflict with each other, and in such cases, Obama has provided no guidance on how to resolve the conflict. A cold-eyed realist such as John Mearsheimer could say that national security trumps or should trump moral responsibility in all such cases: There is nothing “core” about moral responsibility when the chips are down. If that’s what Obama was really saying, then one could chalk it up to posturing—a president claiming moral credit for seeming to take a position he has no real intention of backing up with action.

But this is a willfully perverse reading of Obama’s statement. He did not say what he said in order to relieve the United States of all responsibility for taking preventive action with regard to mass atrocities. On the contrary, his intention was plainly to elevate the importance of such preventive action within the government. His statement came in the context of the establishment of a new Atrocities Prevention Board, an interagency body that would meet periodically to assess risks in particular countries and develop policies to mitigate them.

Meanwhile, the signal contribution of the Trump administration to date on the relationship of moral responsibility to national interest has been what one might describe as the cessation of moralizing. President Trump himself stands apart from his modern predecessors in generally eschewing appeals to morality in his public comments, preferring to justify himself by recourse to a kind of callous pragmatism. Yet this tough-guy act entails a bit of posturing of its own. Recall that Trump was visibly moved by children suffering in Syria from a chemical attack by the Bashar Asad regime—to the point of authorizing a punitive military strike. Even a document as interest-focused as his 2017 National Security Strategy gestures at strengthening fragile states and reducing human suffering. And at Trump’s National Security Council, Obama’s Atrocities Prevention Board is in the process of undergoing a rebranding as the more modestly named Atrocity Warning Task Force, but its function appears to be substantially the same.

While putting “America first” seeks to subordinate moral responsibility to national interest, the moral aspect of policy choices never entirely goes away. In fact, the president seems to take the view that U.S. moral authority has its true origin in putting America first—and being very good at it. Without the strength that comes from serious American cultivation of its security interests, moral authority means nothing. And while many argue that Trump is sui generis, it is hard to miss that the current Commander in Chief has tapped into a kind of popular moral fatigue that was already brewing under Obama.

The tension between moral responsibility and national security interests is real, and it cannot be resolved either by seeking an identity between the two or simply chucking out moral considerations in their entirety. The key to making sense of Obama’s sweeping statement is to view policies of prevention not as either a matter of moral responsibility or national security interest, but always as a matter of both. There is no separable national security argument about how to handle cases in which large numbers of lives are at risk without considering the moral implications of doing so or failing to do so, nor is there a moral argument that can govern action apart from national security interests. As a practical matter for policymakers, the question of what to do always takes place at the intersection of moral responsibility and national security interests.

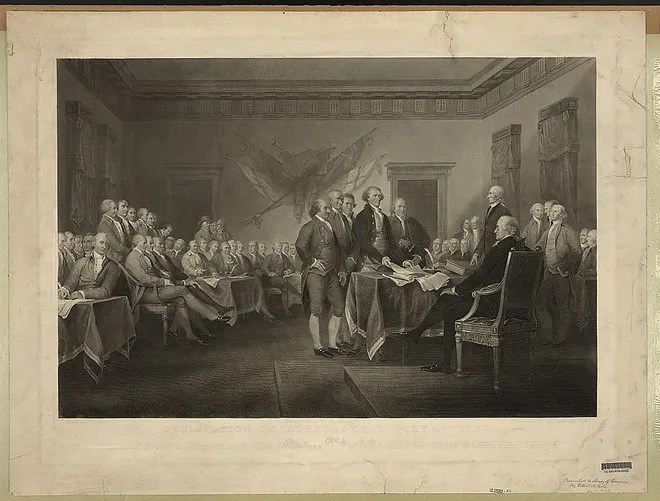

Generally speaking, there are three broad categories of ethical reasoning in deciding what one should do. As applied to the United States or other governments, a “consequentialist” perspective asks whether the likely outcome of what we do is good for our country and our friends and bad for our enemies; a “deontological” or rule-based ethical perspective tells us to do the right thing; and a “virtue-ethics” perspective asks us to take action that reflects our values and will reflect well on us as a country. Moral authority, and with it “moral responsibility” of a “core” nature or otherwise, is mainly a matter of the latter two categories of normative reasoning. Perpetrating atrocities is wrong, and those with the capacity to stop it should do so: That’s a general rule of conduct. Because the Declaration of Independence founded the United States on the principles of the “unalienable Rights” of all human beings to “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness,” Americans should take action where possible to secure those rights for others when they are being violated on a mass scale; our self-respect requires us to take action rather than turn away: That’s a virtue-ethics perspective.

But something else is already implicit in these imperatives, at least at the extreme where the United States contemplates taking military action to halt a genocide in progress. Even in response to genocidal activity, no doctrine or rule can oblige the United States to take action that would have suicidal consequences. Nor does self-respect properly understood ever demand suicidal policies. The Latin maxim “Fiat justitia et pereat mundus”—“Let justice be done, though the world perish”—may be an appropriate point of view for an advocacy group working to promote such desired ends as human rights and accountability for abusers with as little compromise as possible. But the principle is no basis for government policy. The United States would not invade Russia to halt genocide against the Chechens, for the simple reason that the possible if not likely consequence of doing so, nuclear war, would be worse. So consequentialism is already present in the rule-based and virtue-based normative declarations about supposed American moral responsibilities; in the preceding paragraph, it arises in such phrases as “those with the capacity to stop” atrocities and “where possible.”

The implicit consequentialism in even a “core moral responsibility” also rescues the rules- or virtue-based normative arguments from a frequently voiced criticism, namely, that they cannot be consistently applied in the real world. Of course they can’t! Once again, we are reasoning about the most extreme form of political violence: mass atrocities currently under way and whether to take action to halt them. The fact that a military response in one such hypothetical could lead to nuclear war does not mean that a military response in all such circumstances would be devastating. Therefore, the fact that one must refrain from responding in certain circumstances out of prudential considerations does not mean one must refrain in all circumstances. The moral reasoning that leads to the conclusion that one should take action is not rebutted by the conclusion that taking action in a particular case is too dangerous. One should take action where one can take action with due regard for prudence. The moral position does not become hypocritical just because it can only be realized imperfectly.

Critics often deride “idealism” of the Wilsonian sort (or the Kantian sort) as wildly impractical. So it can be. But if we consider consequences at the opposite end of the spectrum from nuclear war—that is, where the risks of taking action are negligible to the vanishing point—then we still face a moral question about whether or not to act. And in such circumstances, why wouldn’t the United States act?

Here, a useful analogy is the response to a natural disaster abroad: an earthquake or a tsunami. Offering humanitarian assistance through the U.S. military, for example, is not entirely without risk, but in many circumstances the risk is minimal—perhaps little more than the risk accompanying routine training missions. Because we place a value on preserving human lives, we extend the offer. This is “idealism” in action as well. An American president would be hard-pressed to give a speech to the American people explaining why the United States has no reason to care about lives lost abroad to a natural disaster and no reason to extend assistance to survivors to prevent further loss of life.

Most policy questions, of course, arise in the context of risk to the United States that falls between “negligible” on one hand and “nuclear war” on the other. When atrocities are “hot”—ongoing or imminent—the United States must and will always weigh the risks of taking action to stop them. President Obama’s statement in no way obviated such a necessity. Nor will the calculation ever be strictly utilitarian in the sense of the greatest good for the greatest number: Any American president will put a premium on the lives of Americans, including members of the armed services. To make these common-sense observations is to lay the groundwork for a conversation about whether the United States may be prepared to intervene in a particular situation involving atrocities. There is no “doctrine” that can provide the answer to the question of risks in particular circumstances. Policymakers must and will assess risk on a case-by-case basis.

Moreover, there is no reason to believe policymakers will all arrive at the same conclusion in a given situation. There will likely be disagreement over most cases between the extremes, and some of it will be the product not of differing technocratic assessments of risk but of the predispositions policymakers bring to their positions. These predispositions may be ideological in character or may simply reflect different tolerances for risk affecting individuals’ calculations. Observers often say that the decision to take action is a matter of “political will.” That’s true, but it’s not typically a matter of conjuring political will out of a climate of indifference. Rather, it entails acting against the resistance of opposing political will. When it comes to questions of humanitarian intervention, there will almost always be stakeholders in favor of inaction. Their justification is unlikely to be articulated on the basis of indifference to the lives at risk. Rather, it will be based on the contention that the likely cost is too high—a consequentialist argument based on national interest.

In practical cases, the only thing that can overcome such consequentialist calculation is a moral case. We have seen that such a moral imperative is implicit in the modern reading of the founding principles of the United States—the “unalienable Rights” human beings have, starting with life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. It is no refutation of these principles to note that governments often fail to respect them. Governments should respect them and should enact laws and enforce policies that protect individuals from abuse. Ultimately, the utility of Obama’s statement was not in establishing the “national security interest” of the United States in preventing atrocities as such, but in reminding policymakers of the moral questions involved in and underlying national interests.

Steps toward the institutionalization of this moral perspective—to create within the U.S. government redoubts where officials begin with the presumption that lives are worth saving—are a welcome addition to policymaking processes that often find it easier to pretend that national security interests are indifferent to moral considerations. Obama’s Atrocities Prevention Board represents such an addition. Another addition was Obama’s requirement for the Intelligence Community to make assessments of the risk of atrocities in other countries. Congress has weighed in with the near-unanimous passage of the Elie Wiesel Genocide and Atrocities Prevention Act, which President Trump signed into law in January. The legislation included support in principle for a dedicated interagency prevention process such as the APB, mandated training for select Foreign Service Officers, and required the executive branch to report to Congress on prevention efforts. All of these initiatives are ways of affirming that the human element matters in considerations of national interest, just as the imperatives of national interest in some cases circumscribe acting out of the best of moral intention.

And it is here, finally, that the most important aspect of the prevention/protection agenda comes into sharper relief. So far, we have mostly been looking at hard cases: where atrocities are ongoing, perhaps on a mass scale, and the only plausible way to halt them is through military intervention, with all the risk it entails, and perhaps also with no certainty of success. We have contrasted an extreme such “nuclear war” scenario with nearly risk-free humanitarian disaster relief, while noting that most “hot” atrocity situations fall somewhere in between.

In all these cases, we have been analyzing situations involving ongoing atrocities. A “prevention” policy in such circumstances entails at best prevention of furtherloss of life—a worthy moral goal subject to prudential calculations of risk. But a “prevention” agenda is much broader. Its purpose is to prevent atrocities, or conflict more broadly, from breaking out in the first place. This process has two elements: first, identifying countries at risk; second, devising and implementing policies to reduce it.

Once again, consideration of the matter through the perspective of a natural disaster is illustrative—in this case, an epidemic. Ebola is an often-deadly infectious disease, an uncontrolled outbreak of which could consume lives on a large scale. Everyone knows this. We also have a general idea of where the disease might break out. Medical doctors and epidemiologists have studied the problem and devised strategies to contain an outbreak. They have briefed public health officials in countries at risk and have sought to overcome any self-interested resistance to acknowledgment of the problem and the need for planning and training to cope with an outbreak.

Political violence is, of course, more a matter of human volition than an epidemic, but some of the structure of the problem is similar. To the extent political conflict has the potential to turn violent but has yet to do so, it resembles a known deadly pathogen to which human beings will fall prey, potentially in large numbers, should it break out. But human beings are not helpless in dealing with such a problem. They need not wait idly by, leaving the possibility of an outbreak to fate. There are strategies for containment that have proven effective in past cases. There are best practices in terms of the standard of medical care, and there are protocols for caregivers to reduce the possibility that they will contract the disease from the patients they are treating. What is more, all involved are aware of the acute danger of the problem, the need to address it seriously, and the importance of learning lessons from past successes and failures.

All of these elements are present in cases of potential conflict, including conflict of the worst sort—mass atrocities and genocide. A fundamental requirement is expertise—first, the equivalent of epidemiologists, individuals skilled in identifying potential sources and precursors to conflict and political violence and strategies to prevent or contain it; second, the equivalent of doctors, those who implement and further refine policies designed to address the sources of risk and to disrupt the precursors to violence. This requirement entails the commitment of resources in developing and coordinating expertise as well as in implementing prevention policies.

A second major requirement is the willingness to put the expertise to use—the political question we have been assessing throughout. With regard to “prevention” in the sense in which we are now taking the term, however, we are no longer looking at the possibility of putting Americans and others in harm’s way, or at least no more so than that risk faced by U.S. diplomats operating in challenging countries. The “risk” is simply the opportunity cost of resources devoted to the cause of prevention—the sacrifice of whatever else might be paid for with dollars going to prevention efforts.

Moreover, just as public health officials look at the dangers of failing to contain an outbreak of disease—another aspect of risk—so policymakers dealing with prevention must look at the potential costs of the failure of prevention efforts. The worst toll of violent conflict comes in the form of human lives lost, but that is hardly the only cost. The resources required to halt a conflict once it is under way and promote reconstruction and reconciliation in its aftermath are vastly greater than the sums required to assess risk and devise and implement prevention policies—a point well understood with regard to epidemics.

Epidemics don’t respect national borders, and neither do some conflicts and potential conflicts. Many potential conflicts, however, are specific to particular countries, and it is unsurprising that policymakers tend to view them through this prism. The history of international politics is more than the sum of all bilateral interactions between governments, but that sum represents the largest component of the history. Organs of the U.S. government that deal with foreign affairs—from the State Department to the Defense Department to USAID to the Intelligence Community to the National Security Council and beyond—are typically organized regionally and then typically by country, as is the interagency process by which they seek to coordinate their efforts to create government-wide policy. The cumulative effect of this mode of organization is to create substantial reservoirs of country expertise inside the government, and this is a very good thing.

But to deal with a potential epidemic, you need not only experts on countries in which epidemics may break out. You need a means of identifying which countries are at greater or lesser risk of epidemic—which means you need experts on epidemics and their causes, or epidemiologists. And you need experts on what to do if an epidemic does break out, public health experts and responders—expertise that cannot wait to be assembled until a breakout actually occurs. And you need experts in how to treat the victims of the epidemic—doctors. In the case of political violence and conflict, you need expertise in identifying potential steps to address drivers of conflict and to disrupt precursors, a task conceptually similar to the development of a vaccine. And of course, once you have these expert human resources in place, you really do need country experts to provide the necessary local context and to adapt general principles and policies to specific cases.

These are the prevention resources the U.S. government needs—and has taken some strides to develop, however incompletely and perhaps without as much systematic attention as the magnitude of the challenge requires. The question of a “national security interest” in prevention in this sense is really nothing other than the question of why we have a government that deals with foreign capitals, regional and international organization, and other entities abroad at all. The United States operates about as remotely from Star Trek’s “prime directive” as is imaginable. “Observe but do not interfere” is not the American métier (nor, for that matter, was Captain Kirk much good at observing the prime directive on behalf of the United Federation of Planets; his moral sense kept coming into play).

There are numerous ways of conceptualizing aspects of or the totality of the problem of political violence and its prevention. Some of them, in fact, have developed into rich policy niches offering great practical insight and guidance. We began here with an area I have spent some time on over the past 15 years, namely, trying to improve the ability of the U.S. government to prevent genocide and atrocities, as well as to improve international coordination of such efforts. But that’s just one aspect. To name a few more: conflict prevention, post-conflict stabilization and reconciliation, peace-building and promoting positive peace, pursuing the Millennium Development Goals and promoting sustainable development more generally, promoting resilience, capacity-building in fragile states or failed or failing states, promoting human rights, promoting effective governance, halting gender-based violence and promoting gender equity, countering violent extremism, human protection, the responsibility to protect (R2P), and promoting accountability as deterrence.

Practitioners in these areas may object, but I would submit that none of them is quite as advanced in its mastery of the policy questions on which it focuses as the epidemiologists, doctors and public health officials are on the problem of preventing an outbreak of a deadly infectious disease. This is not a criticism, but an acknowledgment of several major differences: First, humanity has had a clear idea of the problem of epidemics for centuries, whereas many of the concepts under the “prevention” umbrella listed in the paragraph above are of fairly recent origin as policy matters. Second, as noted previously, though human and governmental responses to a potential epidemic are volitional in much the same way prevention policies are, the diseases themselves are not; political violence or conflict is always volitional, and human motivations are complicated. Third, the downside risk of an outbreak of a deadly infectious disease is vivid in the public imagination and therefore obviously something worth the serious attention and resources of governments, international and regional organizations, nongovernmental organizations, and expert individuals. Conflict and political violence, prior to their eruption in actual killing, are murkier possibilities.

The prevention agenda is also hobbled by what we must acknowledge as an epistemological problem: How do you prove something did not occur as a result of a given policy choice? The failure of prevention is easy to discern, from Rwanda to Syria. Success is more elusive.

From my point of view, a serious examination of the evidence demonstrates that NATO’s military intervention in Kosovo prevented ethnic cleansing, mass atrocities, and possibly genocide. But this was a case where the atrocities were already under way and subsequently stopped. Likewise, a dozen years later, NATO’s Security Council-authorized bombing campaign in Libya prevented the forces of ruler Muamar Qaddafi from wiping out the opposition in Benghazi and exacting the reprisals he threatened on its civilian supporters.

But some scholarship has questioned whether Qaddafi really intended to engage in mass atrocities, thus the necessity of the intervention on its own terms. And, of course, following the fall of Qaddafi, Libya rapidly sank into violent chaos, a situation neither NATO nor its member countries, including the United States, was prepared to prevent, at considerable human cost. Interventions on this scale are rarely simple and one-off: Save the civilians in Benghazi. Intervening sets in motion a chain of events whose end is rarely known at the beginning.

These, of course, are the “hot” cases. The broader prevention project we are considering here aims to address causes of and derail precursors to political violence well before it breaks out. Its activities take place farther “upstream” from such potential violence. That just makes the success of prevention harder to demonstrate.

Harder, but not impossible. And the farther upstream one is from actual violence, the more closely prevention policies seem to resemble each other across the broad conceptions of the prevention of political violence enumerated above. Once violence has broken out, perspectives may diverge; debate still persists over whether bombing Nazi death camps in 1944-45 would have saved lives in sufficient number to justify diverting resources from the military objective of winning the war as quickly as possible. But in the context of a list of countries ranked by risk of bad potential outcomes in the future, the policy interventions from differing perspectives are similar. Potential ethnic conflict, for example, has shown itself open in some cases to amelioration by programs fostering dialogue between relevant groups, and this is true whether the stated priority is conflict prevention, human rights, gender, or societal resilience.

The fundamental point with regard to a prevention agenda is that a policy toward country X is incomplete without one. The U.S. government, as a matter of national interest, conducts assessments of political risk worldwide, typically at the country and regional level. Two conclusions follow: First, the risk assessment should draw on expertise across the full spectrum of the ways in which political violence manifests. Second, the purpose of risk assessment isn’t merely to avoid surprises; it’s to try to avert potential bad outcomes that are identifiable now.

That we are so far able to do so only imperfectly, with regard both to our processes for identifying and ranking risk and to our policies for mitigating it, is no reason to pretend we don’t care about this moral aspect of our national security interests. It’s reason to work to get better at the task.

This article was originally published on August 29th in The American Interest